- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

- cross-posted to:

- [email protected]

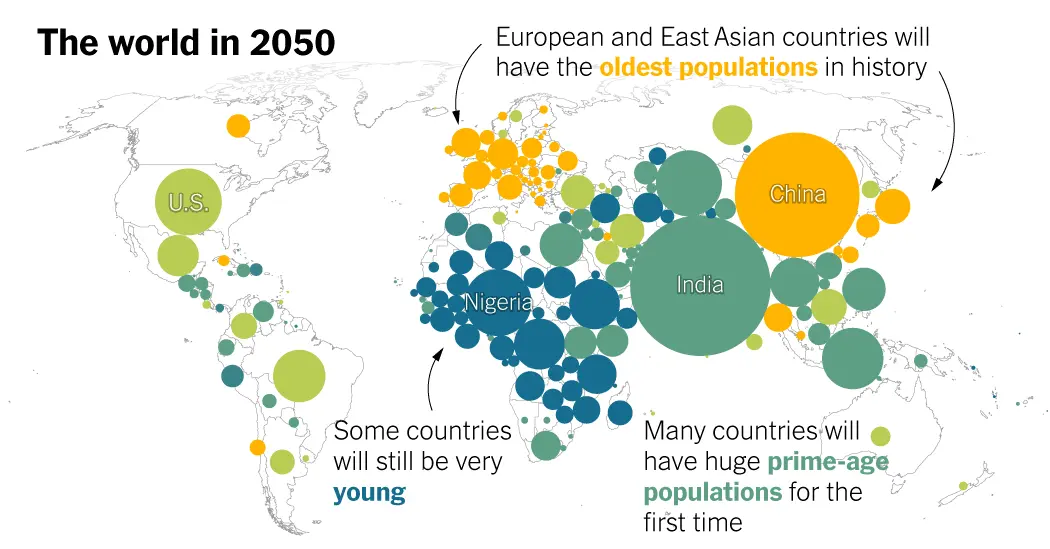

- World demographics have changed: Europe is shrinking, China and India are aging.

- By 2050, people aged 65+ will make up almost 40% of the population in parts of East Asia and Europe.

- An aging world is a triumph of development, but demographics do not guarantee economic growth.

- Aging countries must rethink pensions, immigration policies and life in old age.

- Asian countries are aging faster and getting rich earlier.

- In low-income countries, workers are not protected by a secure pension system.

- Aging is a huge achievement despite the challenges.

- The choice of behavior and public policy is of great importance for the future of society.

Source: Times analysis of U.N. World Population Prospects

As in many young countries, birth rates in Kenya have declined drastically in recent years. Women had an average of eight children 50 years ago, but only just over three last year. Demographically, Kenya looks something like South Korea in the mid-1970s, as its economy was beginning a historic rise, although its birth rate is declining somewhat more slowly. Much of South Asia and Africa have similar age structures.

The upside is enormous.

A similar jump in the working-age population may explain about a third of the economic growth through the end of the last century in South Korea, China, Japan and Singapore, according to the best estimates — an enormous amount of economic growth.

Young populations

Working age

Old populations

1990

Oldest regions

Eastern Asia

Ages:

Large working-age population

Northern America

Ages:

Large working-age population

Australia and New Zealand

Ages:

Large working-age population

Countries shown are those projected to have a population of 1 million or more by 2050, according to U.N. projections. Ages are shown as five-year averages. Regions are based on U.N. classifications.

Many of these demographic changes are already baked in: Most people who will be alive in 2050 have already been born.

But predictions always involve uncertainty, and there is evidence that sub-Saharan African countries’ fertility rates are dropping even faster than the U.N. projects — meaning that those African countries could be even better positioned in 2050 than currently expected.

But without the right policies, a huge working-age population can backfire rather than lead to economic growth. If large numbers of young adults don’t have access to jobs or education, widespread youth unemployment can even threaten stability as frustrated young people turn to criminal or armed groups for better opportunities.

“If you don’t have employment for those people who are entering the labor force, then it’s no guarantee that the demographic dividend is going to happen,” said Carolina Cardona, a health economist at Johns Hopkins University who works with the Demographic Dividend Initiative.

East Asian countries that hit the demographic sweet spot in the last few decades had particularly good institutions and policies in place to take advantage of that potential, said Philip O’Keefe, who directs the Aging Asia Research Hub at the ARC Center of Excellence in Population Aging Research and previously led reports on aging in East Asia and the Pacific at the World Bank.

Other parts of the world – some of Latin America, for example – had age structures similar to those East Asian countries’ but haven’t seen anywhere near the same growth, according to Mr. O’Keefe. “Demography is the raw material,” he said. “The dividend is the interaction of the raw material and good policies.” The Challenges of Aging 50 oldest countries in 2050

Source: U.N. World Population Prospects

Today’s young countries aren’t the only ones at a critical juncture. The transformation of rich countries has only just begun. If these countries fail to prepare for a shrinking number of workers, they will face a gradual decline in well-being and economic power.

The number of working-age people in South Korea and Italy, two countries that will be among the world’s oldest, is projected to decrease by 13 million and 10 million by 2050, according to U.N. population projections. China is projected to have 200 million fewer residents of working age, a decrease higher than the entire population of most countries. Large countries with the highest share of population 65 or older by 2050

Source: U.N. World Population Prospects 2022

To cope, experts say, aging rich countries will need to rethink pensions, immigration policies and what life in old age looks like.

Change will not come easy. More than a million people have taken to the streets in France to protest raising the retirement age to 64 from 62, highlighting the difficult politics of adjusting. Immigration fears have fueled support for right-wing candidates across aging countries in the West and East Asia.

“Much of the challenges at the global level are questions of distribution,” Dr. Myrskylä said. “So some places have too many old people. Some places have too many young people. It would of course make enormous sense to open the borders much more. And at the same time we see that’s incredibly difficult with the increasing right-wing populist movements.”

The changes will be amplified in Asian countries, which are aging faster than other world regions, according to the World Bank. A change in age structure that took France more than 100 years and the United States more than 60 took many East and Southeast Asian countries just 20 years.

Not only are Asian countries aging much faster, but some are also becoming old before they become rich. While Japan, South Korea and Singapore have relatively high income levels, China reached its peak working-age population at 20 percent the income level that the United States had at the same point. Vietnam reached the same peak at 14 percent the same level.

Pension systems in lower-income countries are less equipped to handle aging populations than those in richer countries.

In most lower-income countries, workers are not protected by a robust pension system, Mr. O’Keefe said. They rarely contribute a portion of their wages toward retirement plans, as in many wealthy countries.

“That clearly is not a situation that’s going to be sustainable socially in 20 years’ time when you have much higher shares of aged population,” he said. “Countries will have to sort out what model of a pension system they need to provide some kind of adequacy of financial support in an old age.”

And some rich countries won’t face as profound a change — including the United States.

Slightly higher fertility rates and more immigration mean the United States and Australia, for example, will be younger than most other rich countries in 2050. In both the United States and Australia, just under 24 percent of the population is projected to be 65 or older in 2050, according to U.N. projections — far higher than today, but lower than in most of Europe and East Asia, which will top 30 percent.

Aging is a tremendous achievement despite its problems.

“We’ve managed to increase the length of life,” Dr. Myrskylä said. “We have reduced premature mortality. We have reached a state in which having children is a choice that people make instead of somehow being coerced, forced by societal structures into having whatever number of children.”

People aren’t just living longer; they are also living healthier, more active lives. And aging countries’ high level of development means they will continue to enjoy prosperity for a long time.

But behavioral and governmental policy choices loom large.

“You can say with some kind of degree of confidence what the demographics will look like,” Mr. O’Keefe said. “What the society will look like depends enormously on policy choices and behavioral change.”